By Ron Haskins for the New York Times

Washington – Hardly anyone knows it, but since its earliest days the Obama administration has been pursuing the most important initiative in the history of federal attempts to use evidence to improve social programs.

Despite decades of efforts and trillions of dollars in spending, rigorous evaluations typically find that around 75 percent of programs or practices that are intended to help people do better at school or at work have little or no effect. Studies of the early childhood education program Head Start and the substance-abuse prevention program D.A.R.E. show that even when there are benefits, they are often modest and not enduring.

As a policy analyst who helped House Republicans design the 1996 welfare overhaul and who later advised President George W. Bush on social policy, I am committed to the principle that the government should fund only social welfare programs that work. That’s why it’s imperative that the new Congress reject efforts by some Republicans to cut the Obama administration’s evidence-based programs. Especially in a time of austerity, policy makers must know which programs work, and which don’t.

A growing body of evidence shows that a few model social programs — home visits to vulnerable families, K-12 education, pregnancy prevention, community college and employment training — produce solid impacts that can last for many years. Here are some examples.

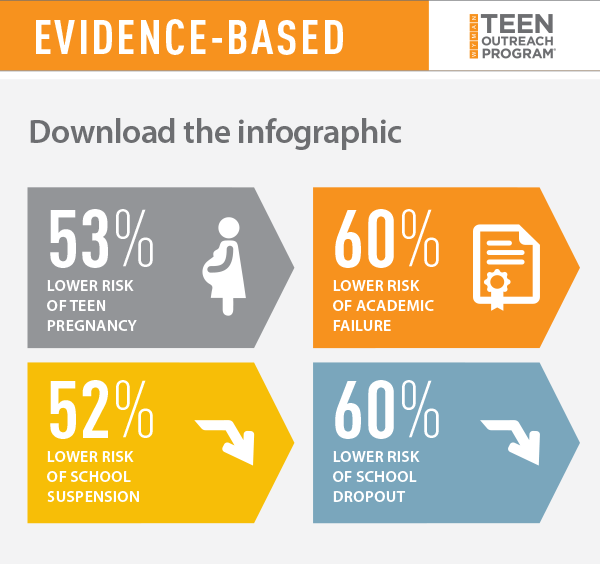

At 24 mostly rural locations in Florida, Wyman’s Teen Outreach Program works with 6,000 ninth graders a year to promote healthy behaviors, life skills and a sense of purpose. Evaluations of the program, which is based on a nine-month curriculum, show that it helped reduce teen pregnancies and lowered the risk of school suspension and dropout.

At 160 elementary schools in low-income communities in California, Colorado, Maryland, New York, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, Washington and the District of Columbia, a program called Reading Partners pairs volunteer tutors with children for twice-weekly 45-minute sessions. An evaluation of the program in 19 schools across three states by the research firm M.D.R.C. found substantial improvements in reading skills.

In Lancaster County, Pa., the Nurse-Family Partnership serves 175 low-income, first-time moms. Nurses start visiting the mothers before birth and continue, with diminishing frequency, until the child is 2. The nurses are trained to form a close relationship with the mother and advise her on prenatal health and child-rearing issues — including smoking and drinking during pregnancy and planning future pregnancies — and on life skills. Typically, 20 to 30 visits are involved. Three randomized controlled trials have shown that the program has major impacts that last at least until the child is 15. The mothers who participated were less likely to abuse or neglect their kids, and more likely to be working, and their kids were more likely to be healthy and ready for school.

Success for All, a comprehensive schoolwide reform program, primarily for high-poverty elementary schools, emphasizes early detection and prevention of reading problems before they become serious. Students of various ages who read at the same performance level are grouped together and receive daily, 90-minute reading classes, as well as one-on-one tutoring and cooperative learning activities. We know it works because a study that randomly assigned 41 schools across 11 states to an experimental or control group found improved reading skills, including comprehension, in students in the experimental group. Most of the students were black or Hispanic, and from low-income families. Success for All was awarded $50 million to more than double its network of schools over five years, to train teachers and to improve effectiveness in new sites.

Expansion of these programs has been possible because the Obama administration, building on work by the Bush administration, has insisted that money for evidence-based initiatives go primarily to programs with rigorous evidence of success, as measured by scientifically designed evaluation. (Continuing evaluation is necessary because programs that work in one location can fail when implemented by new organizations in different locations.) Since 2010, these principles have been the basis for competitive grants to more than 1,400 programs across the country.

Over time, an evidence-based approach should be a prerequisite for any program to get federal dollars. Shamefully, this has not been the case. When John M. Bridgeland led Mr. Bush’s Domestic Policy Council, he was amazed to find 339 federal programs for disadvantaged youth, administered by 12 departments and agencies, at a cost of $224 billion. Very few had been evaluated to determine whether they made a difference.

The evidence-based movement separates the wheat from the chaff. If this movement spreads to more federal programs, especially the big education, employment and health programs supported by formula-based grants, we can expect consternation and flailing as many program operators discover that their programs are part of the chaff.

This is why rigorous evaluation is often unpopular, for politicians in both parties. Historically, Democrats have been criticized for throwing money at intractable problems, while Republicans have been depicted as heartlessly assuming that social spending never works. The truth is, of course, more complex. Since Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society, disjointed, inefficient, poorly implemented social programs have been created and funded without vigorous assessment. Years of failure have taught us that humans are difficult to change.

The Obama evidence-based initiative has charted a new path that could reduce poverty and increase economic opportunity for the disadvantaged. Rather than cut these programs, Congress should extend funding so that successful programs can expand to new sites while programs that are not working are improved or abandoned. Social policy is too important to be left to guesswork.

Ron Haskins is co-director of the Center on Children and Families at the Brookings Institution and co-author of “Show Me the Evidence: Obama’s Fight for Rigor and Results in Social Policy.”