by Nicki Thomson, Senior Director of Research and Learning, and Grace Bramman, Associate Director of Evaluation and Grants

Social connections are foundational to supporting adolescent social-emotional learning and educational success—this foundation is as important to education as ABC’s and 123’s. Years of research tells us that supportive relationships are linked to social-emotional skill development, and in turn, social and emotional skills are key predictors of educational success. Adolescence is a particularly critical period for relationship development, as teens are biologically and developmentally “wired” to seek and manage peer relationships. The quality of these relationships can have far-reaching consequences, including physical, mental, and emotional well-being, and consequently, educational outcomes. Adolescence is also a window of opportunity for change.

The need for social connection has only been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic. Youth are struggling now more than ever with loneliness, mental health issues, and loss of connection to peers and school – impacting their ability to be successful both in and out of the classroom. And this will only increase the short and long-term risks of isolation unless there are concerted efforts to mitigate that risk. Social isolation and lack of social connections in adolescence can impede social- emotional development, which not only affects current educational success and well-being, but also health and well-being into adulthood.

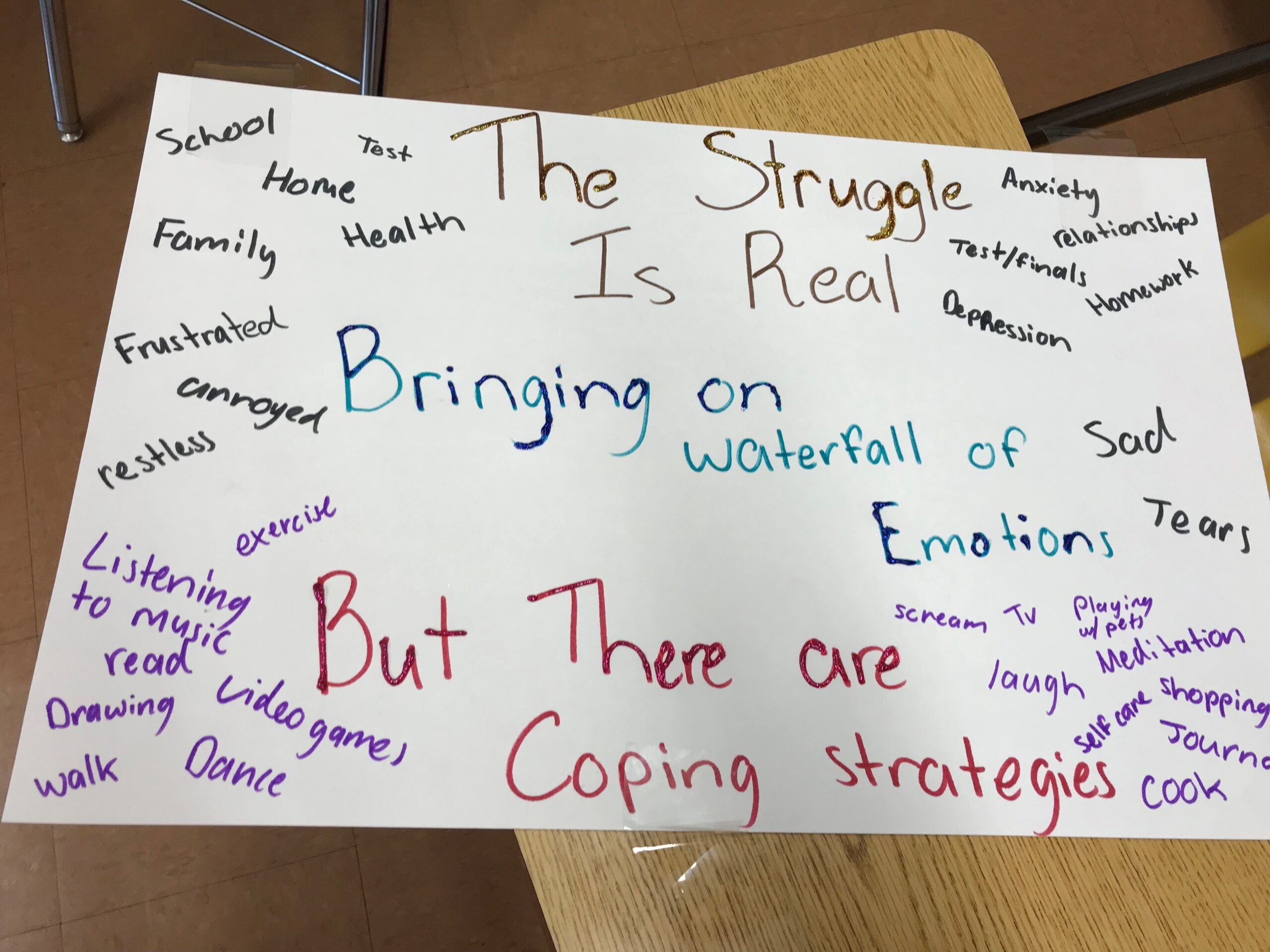

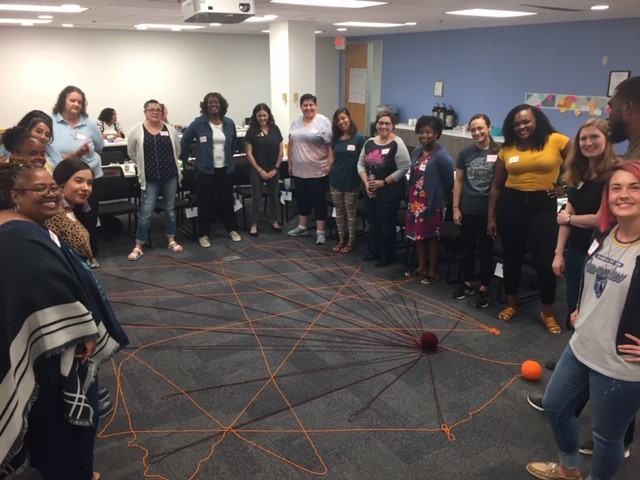

Youth development leaders are learning and innovating to address adolescent social connection needs within the school environment and beyond. An example of an innovation developed by Wyman, a non-profit, youth development organization in St. Louis, Missouri, specifically addresses the need for social connections in adolescence. Wyman’s Teen Connection Project (TCP) was designed to create an experience of connection that fosters healthy relationships and social- emotional learning skills. It is delivered to small groups of high school aged teens (maximum of 15 per group) and facilitated by two trained adults over a 12-14 week program cycle. Program meetings are held on a weekly basis during which the 12 lessons from the TCP Curriculum are delivered sequentially.

The program was designed and tested in a randomized controlled trial through a collaboration between Wyman and Dr. Joe Allen of the University of Virginia. Study results made it clear that the program could successfully address the critical need for social connection in adolescence: teens who received TCP, compared to those who did not, showed improved quality of peer relationships, greater use of social coping (turning to others for support), lower levels of depressive symptoms and higher levels of academic engagement (Allen et al., 2020). TCP was recently added as a SELect program in the 2021 Edition of the CASEL Guide to Effective Social and Emotional Learning Programs (https://pg.casel.org/teen-connection-project).

Exploration of qualitative study data (Nagel, 2020) provided insights into how those social connections are created within the program–high quality facilitation that is characterized by responsiveness to the unique needs of the teens in their groups, such as:

by responsiveness to the unique needs of the teens in their groups, such as:

- Engaging in spontaneous discussion about teens’ interests,

- Building individual bonds between facilitators and teens,

- Talking about shared experiences with being a member of a marginalized group on the basis of race, gender, sexual orientation, or another salient, shared identity,

- Using humor—building on positive comments, enhancing stories, playfully teasing, etc. and,

- Using proactive and explicit redirection (often with humor) when problematic behaviors or disruptive group dynamics arise.

After the study’s completion, Wyman expanded the TCP’s reach through a pilot with 5 organizations located in 5 different states. Evaluation results from the pilot further underscored how transformative the program can be for teens. In addition to positive results on expected outcomes, youth expressed a great deal of positivity about their program experiences. When asked what the best part of participating in TCP was, teens wrote:

That I was able to make new connections as well as learn new things.

Sharing and laughing together as a group. We bonded and connected a little more.

I was able to open up in this group and get to know others I normally wouldn’t speak to in the halls or class.

It has helped me connect to my classmates and learn about them being themselves, rather than just stereotyped as just another student.

Being able to express my feelings to the teachers and being able to connect more with my group mates. Learning how to believe more in myself and learning how to speak up without the fear of being judged.

The pandemic created program delivery challenges for educational and program settings alike—but the importance of ensuring that youth receive the supports and opportunities they need and deserve is all the more necessary. Both Wyman and the University of Virginia (implementing a college-version of TCP, called Hoos Connected) have continued to provide the program virtually, with some adjustments for the virtual space. Data-gathering continues and will help inform learning about the best strategies for delivering high quality programming virtually. We know that any opportunity for youth to help buffer the negative impacts of social isolation can make a powerful, positive difference in their lives.

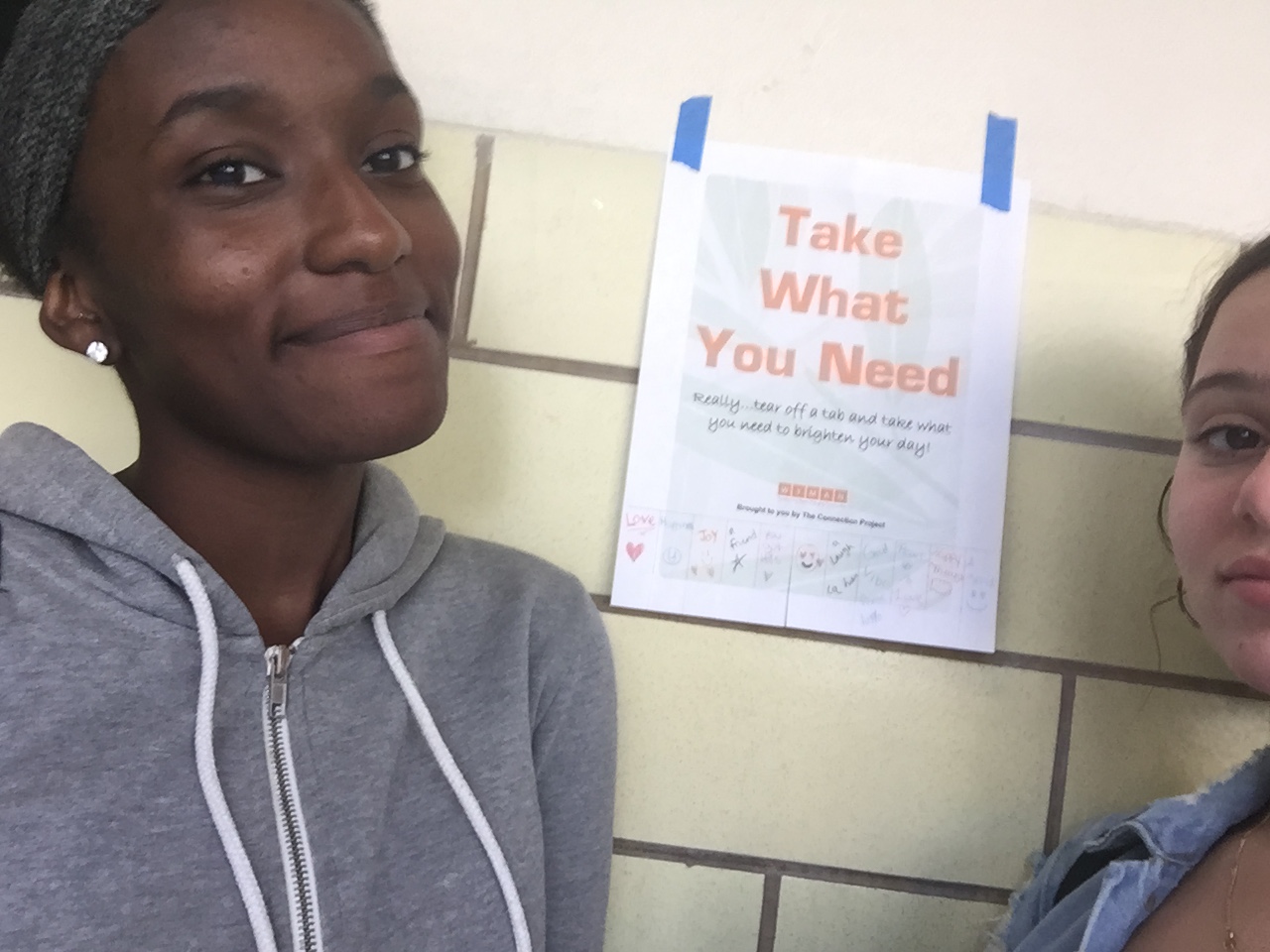

As educators, we are called to support holistic student success – including their social-emotional health – which only serves to reinforce key academic outcomes. It is critical that we expand the conversation around student success to encompass social- emotional learning and the positive peer and adult relationships that facilitate these fundamental competencies. Doing so not only supports student achievement but opens up doors for innovative and potentially life-changing services to reach adolescents at a developmentally crucial period of life in the place where they spend the most time: school. So, what does this look like?

- Expanding and strengthening partnerships between schools and youth-serving non-profits, who specialize in attending to social- emotional needs. The added capacity to school systems can relieve some stress from counselors and social workers and the availability of services or programming in schools can remove some of the barriers students face in accessing community resources.

- Targeted assessment and attentive listening to the needs of young people in schools. Non-profits have a lot to offer in expertise and programming, but they need to exercise intentionality in seeking out partnerships, responding to expressed needs of the schools they partner with, and collaborating to discern appropriate solutions and implementation approaches.

- Investment at all levels – federal, state, and local – in programs for students that support healthy social connections and meeting pressing social-emotional needs. This includes prioritization not only of delivery of effective programs for students, but training and capacity building for adults to better address these needs, and ultimately, build structures into the architecture of the school system to consistently elevate and reinforce healthy relationships and social-emotional health for youth.

Launching these priorities into action will have mutual benefit to youth, school systems, and the broader community. Students who have a foundation of supportive connections and social-emotional skills achieve academic goals and milestones and ultimately become adults who experience long-term health and happiness. While this would already hold true in “normal” times, as we move into recovery from the pandemic, this shift in focus is even more essential. We must consider connections and social-emotional health as a vital and permanent piece of youth success. Our collective experience with COVID isolation has brought these needs to the forefront, but they have always been here – not just as an indispensable mechanism of education, but of the human condition.

Launching these priorities into action will have mutual benefit to youth, school systems, and the broader community. Students who have a foundation of supportive connections and social-emotional skills achieve academic goals and milestones and ultimately become adults who experience long-term health and happiness. While this would already hold true in “normal” times, as we move into recovery from the pandemic, this shift in focus is even more essential. We must consider connections and social-emotional health as a vital and permanent piece of youth success. Our collective experience with COVID isolation has brought these needs to the forefront, but they have always been here – not just as an indispensable mechanism of education, but of the human condition.